Five Common Investor Biases

According to traditional finance theory, the efficiency of markets is underpinned by the assumption that humans act perfectly rationally. Unfortunately, how investors should behave, and how investors actually behave, often bifurcates. This led to the emergence of behavioural finance, which attempts to explain how emotions, heuristics, and past experiences impact our decision-making. We will provide an overview of five common investor biases and the potential implications on portfolio performance.

Overconfidence

As humans, we tend to overestimate our own abilities. A global survey by Visa found that 48 per cent of the 6,000 respondents believed they could recognise a scam. Yet 73 per cent typically responded to terms and phrases used by scammers in messages and emails. In fact, respondents who described themselves as “very or extremely knowledgeable” were more likely to respond to a scam than those who were “somewhat knowledgeable or less”.

Overconfidence can lead to investors disregarding new information or neglecting outside counsel. Investments may end up concentrated in a select few sectors or holdings the investor knows well, but the overall portfolio lacks diversification. Believing he is above average, the investor may try to time the market, something most professionals fail to achieve. At the end of 2022, 81.2 per cent of general Australian equity funds underperformed the S&P/ASX 200 over the previous five-year period.

Familiarity

Familiarity bias is the choice to remain within our comfort zone despite other viable options. This is prevalent in equity allocations, for which Australian investors are typically overweight the local market:

Listed shares represented 29.3 per cent of self-managed super fund (SMSF) assets, compared to just 1.8 per cent for overseas equities;

Among Australian investors, 58 per cent own Australian shares, compared to 15 per cent for international shares;

In a study by FTSE, Australian pension funds held 52 per cent of their equities allocation in domestic shares. This is despite Australia representing just 2 per cent of the FTSE All-World Index.

Intuitively, this makes sense. We invest in companies and brands that are familiar to us such as Commonwealth Bank or Woolworths. Local investors also benefit from the dividend imputation system and franking credits. However, it means investors forego the potential gains and portfolio diversification of investing across geographies.

Overseas markets may rise and fall at different times to Australia, which can reduce portfolio volatility. It also provides exposure to different types of companies. This is important as the Australian equity market has a relatively large weighting towards materials and financials, with a relative underweight in technology. Investors should be mindful of currency, which is an added variable when investing offshore.

Source: FTSE

Loss Aversion

Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman found the pain from losses is twice as strong as equivalent gains. He used the test of flipping a coin with his students to illustrate this point. If the coin landed on tails, the student lost $10. When asked how much compensation would be required to accept this gamble, students wanted $20 or more.

“I've been doing the same thing with executives or very rich people, asking about tossing a coin and losing $10,000 if it's tails. And they want $20,000 before they'll take the gamble.” - Daniel Kahneman

Loss aversion can subsequently lead to conservative portfolio allocations, with investors foregoing the potential for significant gains to avoid any probability of losses. Furthermore, an

investor may hold onto loss-making investments in order to desire realising losses, in the hope that these return to parity – known as disposition bias. Conversely, when markets fall, an investor may opt to sell assets and miss any potential rebound in market prices.

Following The Herd

Herd behaviour is the act of following or accepting the belief of the crowd rather than conducting independent analysis. When a large group of people are involved, it’s unlikely so many people could be wrong. Herding is often encouraged by quick and effortless gains.

Source: CFA

Herding behaviour was voted the number one investment bias amongst investment professionals. It’s easy to fall into the trap of being influenced by peers or new trends, however, following the crowd can lead to poor investment returns. Potential gains may already be realised if there is already a large following. Asset bubbles and subsequently market crashes can occur, most recently evidenced by the fall in the value of cryptocurrencies. Moreover, there are trading costs of moving in and out of the next big thing.

Alfred The Anchor

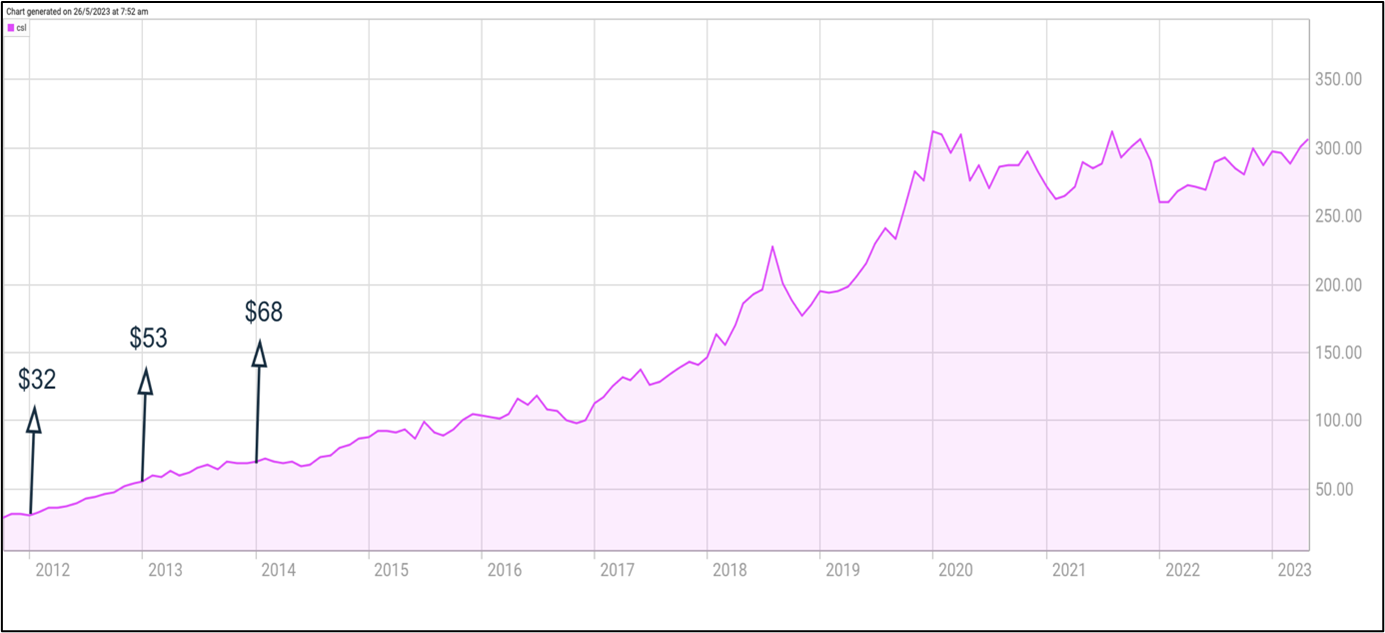

Anchoring refers to when investors use arbitrary information, such as the first share price they see, as a benchmark for future decisions. To illustrate we will use a fictional investor called Alfred Anchor.

At the start of 2012, Alfred’s is considering purchasing CSL shares, which are trading for $32. He decides to wait and see how the share price performs. One year later, the share price has risen to $53. Alfred thinks, “I couldn’t possibly buy CSL now, the share price is 65 per cent more expensive!”. Alfred is anchoring to the first share price of CSL he saw. Instead, he should be determining the value of CSL shares.

Another year has passed, and now the CSL share price is $68 – more than double since Alfred first looked at the company. He sighs. “If only I bought CSL when I first looked at it”. Again, Alfred is anchoring to his initial reference price rather than CSL's prospects and fundamentals. Had he resisted and decided to invest in 2014, he would have made four times his money – even after it had already doubled in the prior two years – with the CSL share price now above $300.

Important Notice:

Zuppe International Pty Ltd t/as Lawrance Private Wealth and The Financial Advice Shop (AFSL No. 532878).

General Advice Disclaimer:

The information and opinions within this document are of a general nature only and do not consider the particular needs or individual circumstances of investors. The Material does not constitute any investment recommendation or advice, nor does it constitute legal or taxation advice. Zuppe International Pty Ltd (ABN 12 628 405 952) (The Licensee) does not give any warranty, whether express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or otherwise of the information and opinions contained herein and to the maximum extent permissible by law, accepts no liability in contract, tort (including negligence) or otherwise for any loss or damages suffered as a result of reliance on such information or opinions. The Licensee does not endorse any third parties that may have provided information included in the Material.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results and current performance may be higher or lower than the performance shown. Therefore, any stated figures should not be relied upon. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s investments, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost.