A Short Story: Adani v Hindenburg

Adani Group is an Indian conglomerate with activities spanning power transportation, infrastructure, renewables, mining and energy. There are seven listed companies bearing the surname of its founder and majority shareholder Gautam Adani, who at one point was the world’s second richest person worth upwards of US$150 billion. Adani himself has close ties with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Both hail from the same state of Gujarat, with Adani’s business activities and new projects helping facilitate Modi’s development of India’s economy.

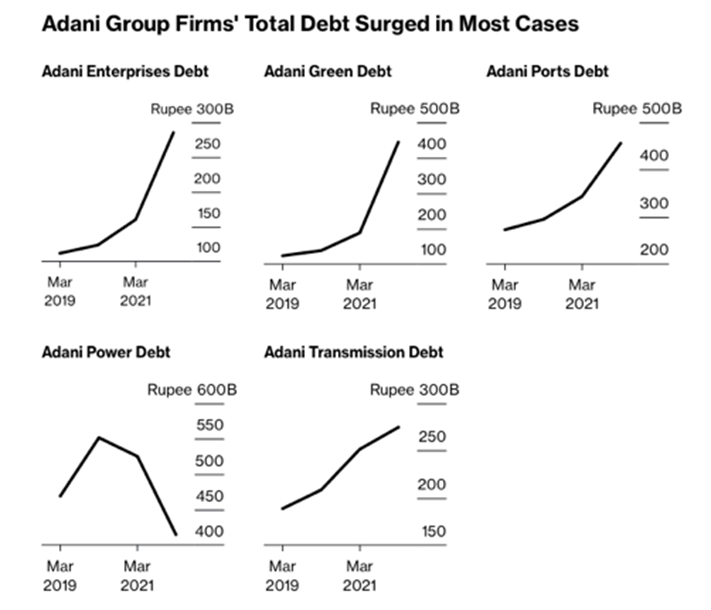

Source CreditSights

Hindenburg Strikes

However, the fortunes of the Adani empire have vanished over the past month after a report by Hindenburg Research accused the company of “brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud scheme over the course of decades”. On January 24, the small US-based investment firm raised several allegations of misconduct including:

Debt − various Adani Group entities have used debt to fund growth projects and acquisitions that potentially place the broader conglomerate at risk;

Offshore entities − shell companies based in Mauritius affiliated with Adani companies and family members were used to manipulate earnings, inflate share prices and conceal ownership;

Investigations – Adani Group had previously been the subject of four government investigations into alleged fraud and corruption;

Auditor – some Adani subsidiaries are audited by a small accountancy firm that audits just one other listed firm;

Valuation – ignoring the rest of the research, the seven key listed entities have 85 per cent down when compared to the valuations of industry peers

Hindenburg disclosed it was ‘short’ Adani – essentially a bet the share price would fall in Adani’s companies and Hindenburg would profit as a result. Since the release of the report, Adani Group companies have lost 50 per cent or over US$120 billion in market value. Gautam Adani’s wealth has more than halved, with planned equity and debt issuances scuttered. Adani published a rebuttal days later, calling the report a malicious combination of selective misinformation and concealed facts. Hindenburg said that Adani failed to answer key questions.

Leverage Concerns

Adani’s phenomenal growth had largely been fuelled by borrowing large amounts of debt. This isn’t uncommon for infrastructure and energy companies. Typically, there is a big upfront spend to build a port or mine before cash begins to flow in the door. The issue is that Adani had taken it to the nth degree. The liabilities of Adani’s ten listed companies add up to $41.1 billion and account for around 71 per cent of total assets. Operating earnings barely support the interest payments on this debt. Hindenburg highlighted that five listed entities have insufficient liquid assets to meet near-term liabilities.

Warren Buffett often recites a quote from his partner Charlie Munger: “There are only three ways a smart person can go broke: liquor, ladies and leverage. Now the truth is – the first two he just added because they started with L – it’s leverage.”

Source Bloomberg

The Dark Arts

Short selling is somewhat of a dark art. To illustrate: a nefarious actor could short a company, release a lengthy and detailed report with any number of claims, profit from the immediate market reaction and be out before investors realise it was all fluff. As a result, short reports aren’t always taken seriously by the market.

If Adani was really massaging the financials, why are its returns and margins so low? It is also hard to reconcile that entities in Mauritius would be propping up the share price of multi-billion-dollar companies without significant trading volumes. That’s not to belittle Hindenburg’s other claims. In fact, a previous report by Hindenburg took down electric truck maker Nikola, whose founder was subsequently convicted of defrauding investors. But investors should keep in mind Hindenburg’s conflict of interest; it wants Adani to fall in value.

The Good and Bad of Conglomerates

Put simply, a conglomerate is a company that owns a portfolio of several different and independent businesses. The most well-known conglomerate on the ASX is Wesfarmers, which owns Bunnings, Officeworks and Kmart in addition to chemical, lithium, health and digital operations. Wesfarmers has beaten the benchmark since listing in 1984, in addition to outperforming over five and ten-year periods.

Source: Wesfarmers Macquarie Presentation 2022

The benefits of owning many companies include the ability to raise finance more easily, weather downturns in one division with performance in others, and share operational and knowledge resources. For investors, it’s an easy way to gain diversification without needing to buy several companies.

The downside of a conglomerate structure is that it is inherently complicated. It’s hard to know precisely what’s going on under the hood, and investors are dependent on management to act as responsible fiduciaries. In 2008, General Electric was the largest company in the world and a beacon of corporate America. Today it’s splitting itself in three after decades of accounting trickery to meet next quarter's numbers at the expense of long-term value.

The takeaway is not to avoid conglomerates but to be conscious of the risks. A lack of disclosure, borrowing to fund dividends or acquisitive growth are signs that the underlying divisions may not be resilient.

ESG: Governance

ESG (environmental, social and governance) is an integral part of our investing framework which helps us avoid risk and invest in sustainable businesses. Hindenburg said eight of the 22-person leadership team at Adani are family members. Regarding board composition, the risk management and stakeholder relationship committees only have 50 per cent independent directors.

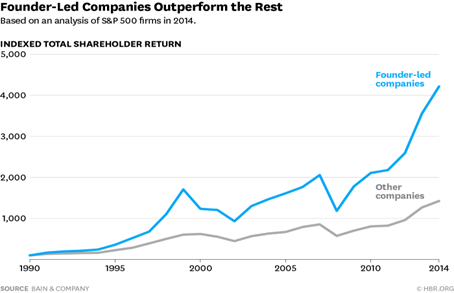

Source: Harvard Business Review

And at the shareholder level, ultimately Gautam Adani has the final say on decision-making given his majority ownership. This alone isn’t cause for concern. There are many family or founder-controlled companies that are successful, such as Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) and Walmart. Indeed, several studies demonstrate that founder-led companies outperform non-founder peers.

However, Adani subsidiaries and family members have faced several investigations by regulatory agencies. Moreover, there is added risk when investing in developing markets as they may not have the same level of regulatory oversight or corporate governance standards. Like conglomerates, family-owned businesses shouldn’t be avoided. But investors must be mindful of the risk when investing in assets and jurisdictions that are not well understood or developed.

Enduring Wealth

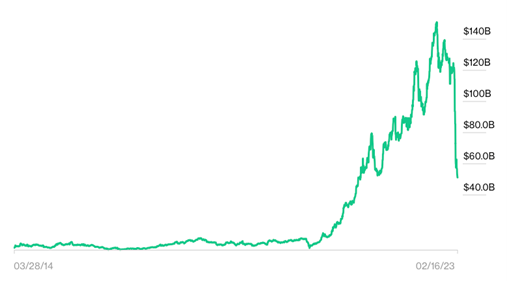

The chart below illustrates Gautam Adani’s net worth since early 2014. His wealth sharply increased around the onset of the pandemic and roared higher for the next three years as debt-fuelled pheromonal growth. The seven listed entities' average share price increased by 819 per cent return over that following three-year period. Investors, enticed by the rapid gains, and allure of profiting from the rise of India, saw Adani Group as a quick and easy bet – until it wasn’t.

Source: Bloomberg Billionaire’s Index

We take a long-term approach to investing at Lawrance Private Wealth. Short-term gains are welcomed, but we believe the most repeatable and proven method of building enduring wealth is over time. To illustrate why we will again return to the Oracle of Omaha.

Today, Warren Buffett’s net worth is $108.0 billion. Of that, $107.7 billion was accumulated after his 50th birthday. He is revered as one of the greatest investors of all time. However, the secret to his wealth is not wonderful returns. Instead, he allowed compounding to work its magic over many years and decades.

Important Notice:

Zuppe International Pty Ltd t/as Lawrance Private Wealth and The Financial Advice Shop (AFSL No. 532878).

General Advice Disclaimer:

The information and opinions within this document are of a general nature only and do not consider the particular needs or individual circumstances of investors. The Material does not constitute any investment recommendation or advice, nor does it constitute legal or taxation advice. Zuppe International Pty Ltd (ABN 12 628 405 952) (The Licensee) does not give any warranty, whether express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or otherwise of the information and opinions contained herein and to the maximum extent permissible by law, accepts no liability in contract, tort (including negligence) or otherwise for any loss or damages suffered as a result of reliance on such information or opinions. The Licensee does not endorse any third parties that may have provided information included in the Material.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results and current performance may be higher or lower than the performance shown. Therefore, any stated figures should not be relied upon. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate so that an investor’s investments, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost.